As my children entered their teens, I noticed that they and their friends were expressing Islam in a manner that was quite different from their parents. A rather sensible version.

When we had opened the doors of our mosque in Staten Island in 1990, Muslims of various ethnicities filled up the prayer hall—Pakistani, Indian, African-American, Arab, Turkish . . . . Each group was expressing the faith in their own way. Some women wore the hijab, others did not; some men would shake hands with a women, others would place their hand on their heart; some men made eye contact with women, others lowered their gaze; some celebrated the prophet’s birthday, others did not. Each group was convinced that their way was the Islamic way. That was when my husband and I realized that so much of our practices are a product of our culture and traditions, yet we attribute it to religion.

I recalled an incident of my childhood. In Pakistan, women in the 1960s did not wear the hijab, but their legs were always covered—still are. A delegation of Jordanian women was visiting. They wore headscarves, and sported knee length skirts.

“Your legs are not covered,” a Pakistani woman said to the Jordanian.

“Your hair are not covered,” said the Jordanian.

Each rebuked the other for violating the Muslim dress code. Each had defined the Islamic principle of dressing modestly according to their culture and tradition.

Noticing the confusion this circumstance had created in our mosque, my husband and I concluded that the only way to distinguish what was religion from what was cultural, was to go to the source—the Quran; separate the divine from the man-made; and wrap it in an American flag, in the hues of red, white, and blue. What emerged was an American-Muslim identity, one that is wholly Islamic and wholly American; one that our American born children have embraced organically.

What I mean by that is: There are some things that have not changed, and some that have. What hasn’t changed are the core beliefs: Belief in One God, Prayer—five times a day, Charity, Fasting during Ramadan; and Hajj—the pilgrimage to Mecca; belief in the prophets, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Peace be Upon all of them; belief in the revealed books—Torah, Psalms, Bible, and The Quran; and belief in the angels and the Day of Judgment. What hasn’t changed are the core values: respect for parents, treat others as you would like to be treated, compassion, mercy, forgiveness—universal values.

What has changed is how they express their faith. They dress American—the Pakistani shalwar kameez, Indian saree, Arab jalabiya are book-ended in the closets for traditional weddings. At weddings, the religious ceremony is no longer held in private. When I got married, I was upstairs in my bedroom with the girls; my husband-to-be was downstairs in the living room with the guys; and my uncle was running up and down the stairs, getting the consent and signatures, marriage contract in hand. The marriage party was held the next day in a banquet hall and I finally got to sit with my groom. Today, in the ballroom of the hotel, the bride and groom are seated on the stage, and the religious ceremony is held in the presence of hundreds of guests. Very American, very Islamic. (In Islam, marriage is a public affair.) The bride wears white. I wore red—that was the culture. The bride no longer has to change her name after marriage. I changed my name from Sabeeha Akbar to Sabeeha Rehman, not because it was the Islamic way (which it wasn’t), but because it was the British way. Pakistan was once a British colony. Today, Muslim women have discovered that it is entirely Islamic to keep one’s father’s name—a matter of lineage. Besides, you can find your friends on Facebook. How they give thanks has changed. In Pakistan giving thanks was celebrated by distributing halva desert to neighbors. Now we have Thanksgiving, Mothers Day, Fathers Day…very American, very Islamic. (The second commandment after belief in one God, is to respect your parents.) What has changed is the man that holds the microphone. Until a decade ago, mosques could not find a local imam, and had to import imams from the Old Country. These imams didn’t speak the language, didn’t know the local culture, and our children couldn’t relate to them. Now, we have seminaries where American-born youth are seeking religious education, are exploring contemporary issues, and are transmitting an American brand of Islam. When the first generation of immigrants established mosques, they did it along the lines of country of origin; Pakistani/Indian mosque, Albanian mosque, etc., as these venues also served as cultural and community centers where immigrants could converse in their first language, dress traditional, and exchange notes on politics ‘back home.’ Our children will cut across ethnic lines and establish American mosques, where the conversation will be local and the causes American.

But most of all, the role of women has changed—in the home and in the mosque. In their private lives, women in America are reclaiming the rights given to them by the Quran, but deprived by the culture of the Old Country. In Pakistan, women never went to the mosque. It was a man’s thing. Here, they are teaching, setting the curriculum, sitting on boards, even presiding. All very Islamic and very American.

But something hasn’t changed, and will not change—I hope. The food! American Muslims will continue to relish the kebabs, biryani, shawarma, satay chicken, chai, hummus, halva . . . .

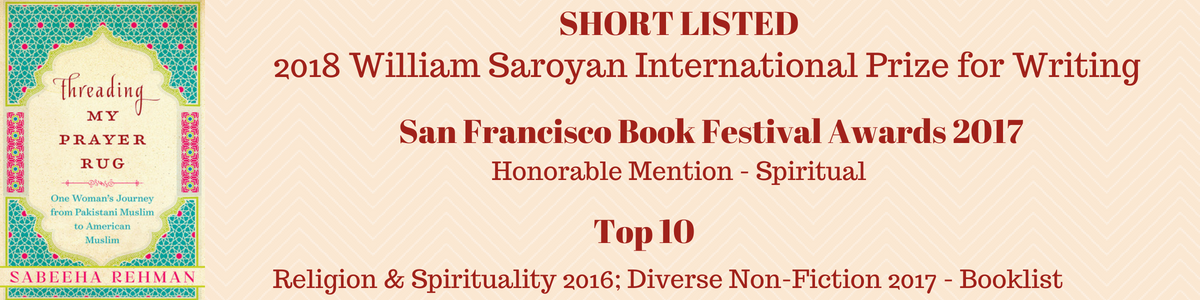

(Excerpts from my memoir 'Threading My Prayer Rug.')