Ramadan is over and yesterday we all celebrated Eid ul Fitr. Children got dressed up in sparkling new clothes, squealed with delight when opening brightly colored gift wrap, counted their cash Eidees that elders handed them, slurped over the sweet sheer khorma, mommies and aunts chirped away in the kitchen, and we ate and ate and ate, making up for the month-long fast. The sounds of Eid Mubarak would fill the house every time the doorbell rang and more visitors walked in.

But for many, Eid was bittersweet. My aunt, the only surviving sibling of my father, passed away days before Eid, my cousin lost her husband, and another cousin died suddenly of heart failure. What was Eid like for them?

When I was growing up in Pakistan, it was the tradition that the grieving family would not observe Eid. The family would go into a state of quiet mourning, remembering and missing their dearly departed. For them there would be no new clothes, no gifts, no visits to families, no feasting, and no greetings of Eid Mubarak. In the days preceding Eid, if anyone inadvertently asked, ‘So, what are your plans for Eid’, the response was, ‘We are not celebrating Eid.’ If someone organized a party on Eid, it was understood that the grieving family would not be observing Eid, and hence you did not want to be disrespectful by issuing an invitation.

All that changed when I came to the U.S. The confluence of Muslims of so many national origins—Turkish, Arab, Indian, Albanian, Indonesian, African-American, African-African—all with their cultural bent to Eid, gave us pause and something to think about. Within years, a new tradition took shape. We woke up to the fact that on Eid—of all days—aggrieved families need the comfort of friends to ease the void left by the departed. We should visit them, be with them, share their pain, and bring some joy in their home. Besides, Eid was a day of thanks—thanks for having fulfilled the obligation of fasting during Ramadan. Why be deprived on a day of thanks! So on Eid, immediately after prayers, the Muslim community would flock to the homes of the family, some bringing sheer khorma, some bringing presents for the children. Families welcomed it. No one was offended.

Decades later my father passed away. I was in Pakistan with him when we laid him to rest. The next day, Ramadan started. I stayed with my mother and sister, and we would fast together. On the night before Eid, families started stopping by and the house was flooded with well wishers. But on the morning of Eid, we were all alone. Mummy had the dining table set up with sheer khorma for the visitors who never came. All around outside, we were hearing happy sounds of Eid, and inside our home, it was quiet. It was as if Daddy had died all over again. We settled into a quiet depression as day descended into evening. I finally pulled my sister up and said, ‘Lets go visit our aunt.’ It is one of the Eid traditions that the young go visit the elders of the family to pay their respects. I couldn’t help complaining to my aunt. ‘It was Eid, we were lonely, and no one came to be with us.’ She explained that here, people visit those who are ‘not celebrating Eid’ on the night before, because on Eid day, they are all dressed up, are in a festive mood, and that is an affront to the families who are grieving. So I gave her my American spin, and she nodded with a look that said, ‘makes sense, but this is how it is.’ When I came home, I said to my sister, ‘I think you should start a new tradition. Next year, start promoting this idea well before Eid, and just do it. Someone has to take the first step.’

That was seven years ago. I just realized that Daddy has been gone that long. Yesterday when I talked to my sister in Pakistan, wishing her Eid Mubarak (actually Eid in Pakistan is today, but that’s another story), she told me that she would be going to visit to my aunt and cousin’s family to be with them on Eid. And many others are doing the same.

The American version of Eid has taken root in Pakistan.

EID MUBARAK

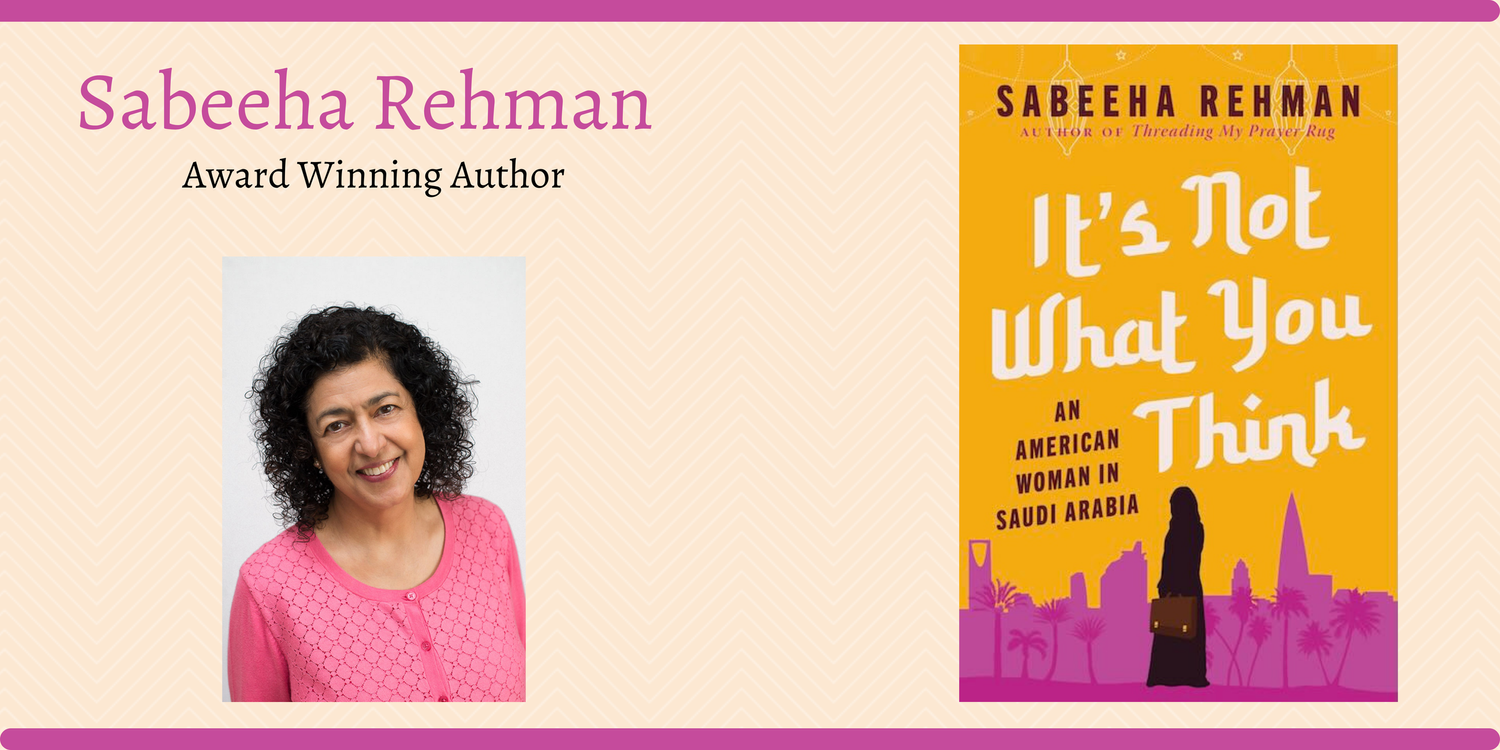

Order here:

At a bookstore near you

and

Amazon (hard cover) Amazon (Kindle)

Barnes & Noble Bookshop.org

Indiebound Books-a-Million

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.