“How many siblings do you have?’ I am asked.

“We are three, my sister, my brother, and I,” I say.

What I don’t say is: I had another sister. She was six months old when she died; I was six.

“How many siblings do you have?” people ask my husband.

“We were eight, now six. My sister and brother passed away a few years ago.”

Why didn’t he say, ‘we are six’?

Why didn’t I say, ‘we were four, now three.’

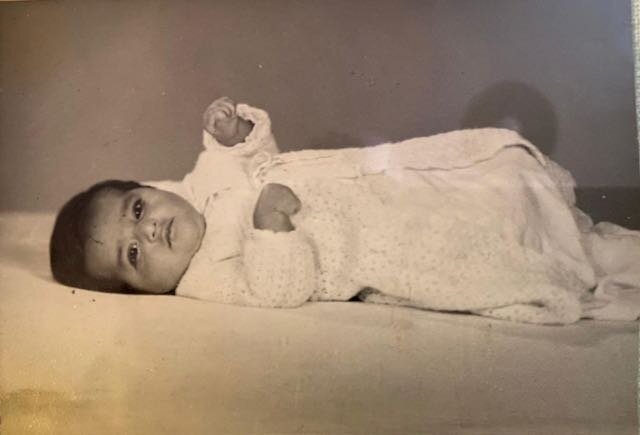

My parents named her Quratulain, which means ‘light of my eyes’. We called her Annie. I do remember her face: she had big round black eyes, a round face, and jet-black hair. I remember the day she died. I had been playing outside with my neighborhood friends, and when I returned home, Daddy was standing outside the house, on the gravel driveway by the front lawn. I ran up to him.

“Annie had been crying and crying for you,” he said, “and now she has died.”

“She has died?” I do remember saying that.

Daddy took me inside. There were ladies gathered in the living room, sitting with Mummy. The room was quiet. He walked up to the table by the window where she lay, a white sheet draped over her small body. Daddy gently uncovered her face. She was still. I looked. Then I ran out to play. When I returned, she was gone, and all the aunties were crying and comforting Mummy. I left the room and went out to play. I don’t remember what happened next, but Mummy tells me that later that night, Daddy broke down in tears. Mummy’s three little girls were now just two. Neena and I, age six and four. Mummy kept Annie’s memory alive, her baby photo framed and prominently displayed on the living room wall. ‘She was the prettiest of my three daughters,’ she would say. She was. Every time Daddy was transferred to the city of Quetta, our first stop would be at the cemetery where Annie lay buried under a tiny mound. “What a short life!” Daddy said once, reading the inscription on the tombstone. I wish I had made note of her birthday, her deathday.

Five years later, my mother gave birth to a boy. Now we were three again.

A few years before Mummy passed away, she visited Quetta for the last time, and like always, made her first stop at Annie’s grave site. While her friends waited in the car by the roadside, she took her time talking to Annie, telling her about her sisters, her brother, how Mummy’s life would have been with her, how it has been without her.

“How many siblings do you have?”

“We are three,” I say.

Like my husband, shouldn’t I say: ‘Four; but my sister died?’ Why do I hold back? Is it because Annie died in infancy, and I grew up with a sister and a brother only? Is it because we were never ‘the four of us’?

Now that I think of it, my husband was one of 10 children. Two died in infancy, two in their sixties. Why doesn’t he say: ‘Ten; but four died? Why does he say: Eight, but two died? Because the two who died in infancy don’t count; but the other two who died in their sixties, do count?

Why do we draw the line at the age of death? Is it because we didn’t make memories of a lifetime together? Because we didn’t play Ring a Ring o’ Roses, ride see-saws, read stories, ride the school-bus, fight and tease, pick the same college, love the same songs; because I didn’t do Annie’s bridal make-up, she didn’t hold my first baby? Because all I remember is her baby face?

I asked my husband, “Why do you say: 8, but now 6?” He says it’s because he grew up among 8, because 8 reached maturity, because he doesn’t remember the two who died—not even a photo; they were not part of his life.

“What did your parents say when people asked, ‘how many children do you have?’” I asked him.

“I guess they said: eight.”

“What did your mother say when asked the same question?” he asked me.

“Three. I suppose because that is all she had in that moment. Because it was too painful for her to say: ‘I had four, but one died. Her name was Annie.’”

Does Annie count?

Ask me again: How many siblings are you?

******************************