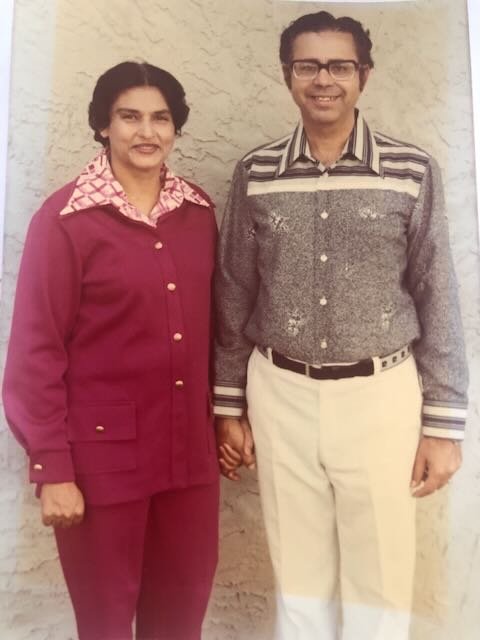

It was 13 years ago today, when we laid Daddy to rest.

Reminiscing, I think about what I admire most about him.

It’s hard when you have so many choices. Be it choosing from an assortment of teas, hand lotion and cheese, a list of books-to-read, or shopping for a pink blouse.

Same dilemma with Daddy; and more so because my admiration continued to shift as the earth made its rotations around the sun. As a child, I was proud of having the only Dad who played with us children; in my teens, I revered how he displayed his admiration for Mummy and wished upon countless stars I too would have a husband who admired me thus. In a culture where mother and daughter were the confidante pair, and fathers were kept at a distance, Daddy refused to recognize those barriers—upholding the mantra: all parents are equal. In the age of arranged marriages, a daughter’s opinion was seldom sought, and for a father to walk up to his daughter and say: “What is your opinion?” was highly unusual. My veneration took on new forms as I matured from being a child to having children of my own; from being one to seek advice, to one who gave advice; Daddy exuding different traits as we glided along our celestial paths, each in our own orbit.

For now, allow me to dwell on one: his stoicism.

Daddy suffered many setbacks in his life, as we all do, but the one that hit him the hardest was losing his vision from his left eye after a cataract surgery went awry. It was a minor surgery, for which he had come to the US hoping to get the best outcome. The surgeon overlooked his myopia and performed a procedure that led to retinal detachment, then major retinal surgery, and eventually, complete loss of vision from the eye.

When he and Khalid returned from his visit with the ophthalmologist, who confirmed that he would never regain his vision, he chose not to reveal the prognosis to me or Mummy. In a few days, Khalid and I were to leave for Mecca to perform the Hajj, and Daddy didn’t want his condition to get in the way of our pilgrimage. He feared that if he told Mummy, her distress would reveal the situation to us. So, he maintained a calm demeanor as they boarded a flight to return to Pakistan.

In the months that followed, Daddy went into depression. When I would call, and if he came to the phone, he could barely talk. We felt helpless. Four months later, he mailed a three-page handwritten letter to me, dated Jan. 18, 1987. His devastation over the loss of one eye was compounded with the stress of potentially losing his job (he kept his job), and the refusal of the Pakistani authorities to pay for his medical expenses in the US. He also felt wronged by the surgeon. I had no words of comfort to offer, other than to acknowledge his pain.

A year later, he brought a lawsuit in the State court in Brooklyn. Khalid and I stayed by his side during the 5-day proceedings. He lost the case. That gave him closure. Or rather, he allowed it to give him closure. He buried the case and moved on.

His recovery is what I find remarkable, and the fact that he was his own counselor and therapist. He no longer talked about his misfortune and carried himself as though he was living in a 20/20 field of vision. Behind his eyeglasses, you couldn’t tell the difference. He walked in his erect military posture. He was careful when descending stairs, but to others appeared to be just an elderly man being sensibly cautious. He used a walking stick adding color to his gait, winging his rod as if he was an officer. If you didn’t know, you couldn’t tell.

He accepted his limitations. He could no longer drive. He gave himself permission to be driven by Aurangzeb, his faithful and loyal orderly; or sit in the passenger seat next to Mummy. He avoided taking walks outdoors after darkness fell. If there were other adjustments he had to make, he didn’t mention them. Except one. I don’t remember when or what the context was, but he said to me one day, as he shook his head lamenting, “I used to read in bed at night before going to sleep. I miss that a lot.” Daddy was a reader. He continued to read the paper and books, but only during daylight hours. The Kindle was a long way off.

He developed new skills and found new hobbies: computer proficiency and writing, becoming a prolific writer. His memoir ‘Reflections’ sits on my bookshelf as does a binder chronicling his ruminations. And he traveled. In his later years, he and Mummy made trips to the Far East, Middle East, Europe, and of course, America. He made it his ‘before I depart’ mission to bond with his grandchildren. He became an American citizenship, so that he could spend time with Saqib and Asim. Daddy was there for their weddings, and all the years in between, until he passed away at age 82.

As I make it past 70, I see him from a new pair of eyes—post-cataract—his resiliency and stoicism is what I revere. He embraced heartache and loss, let it overwhelm him for just a while, and then pivoted to explore what else life, in its infinite capacity for joy, had to offer. And he found it.

Rest in Peace, Daddy